All music has a visual component to it. Whether it is a musician playing an instrument, a music video, a sound installation, or a laptop with spotify open, there is no sound that exists without some sort of visual connection to it. The term ‘audiovisual’, when describing art, does not suggest that the work provides visuals to an otherwise typically non-visible art form. Rather, audiovisual art proposes that its visual and auditory parts are more or less equally in the foreground of the work’s experience. Audiovisual art, in this definition, finds a particularly rich medium in the web – unlike an acoustic musical performance, most relationships between sound and visuals on the web must be consciously programmed by the author, if they are to exist at all.

This article will look at two case studies of web sound art, one with a complex relationship between audio and visuals, and a second with an opposite, extremely minimal approach to audiovisual relationships. Ultimately, this article aims to provide a critical lens to, as well as add nuance to, the visual side of web sound art.

Smooth Operator

A moment in Jazz.Computer.

Jazz.Computer is an interactive song by Yotam Mann, with visuals by Sarah Rothberg. The work is experienced in the web browser, and presents a song whose sections, sounds, visuals, and tempo change according to the user’s scrolling behavior. A study in interactivity, this work’s audiovisual relationship immediately establishes a connection with the user, and develops that relationship as the user continues to engage with the work. Through a simple play button, and several playful dialogue cards in the bottom left (“Scroll the song to advance" and “You’ll never believe what happens next" as two examples) the rules of user engagement with Jazz.Computer are immediately clear. After those conventions are set, the user’s scrolling behavior is provoked; scrolling speed affects the speed of certain animations, and occasionally, unexpectedly, the color change and visual elements present refresh. Like a popular social media platform, or a tutorial level of a videogame, the use of text and symbols in Jazz.Computer are minimal and economical, striving to establish a clear relationship with the user as seamlessly and immersive as possible.

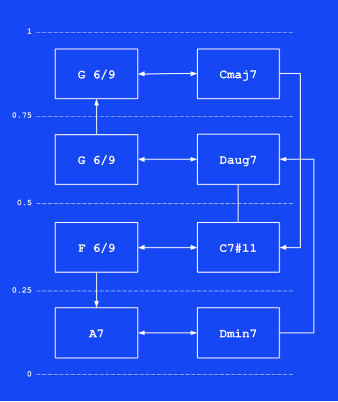

However, the exact relationship between scrolling, musical change, and visual change is less clear, provoking a user’s curiosity, and injecting a built-in drama to the work’s interactivity. To take the harmonies of the music for example, the user’s scrolling behavior triggers change in the harmony. However, while a scrollbar can simply move up or down, the chords are not simply arranged in a linear sequence. Rather, a markov chain is employed to create chord sequences that, while changing at a similar rate to the scrollbar, are different each time, even when the user performs the same scroll behavior twice. There is a similar relationship between scrolling and the visuals. The speed of the scrolling will directly influence the speed of certain animations. However, when scrolling stops, or slows, this doesn’t always result in the animations slowing down. Additionally, scrolling down the page of Jazz.Computer causes colors and images to change. Yet, returning to prior areas of the webpage do not revert those colors and visuals back to their previous states. In both of these examples, the audio and visuals both set up an expectation for a specific relationship between scrolling and audiovisual change. Yet, upon repeat gestures (a common behavior for a user seeking to uncover ‘how the piece works’) it is revealed that the relationship is more complex than it first appeared to be.

A diagram of the harmonic motion in Jazz.Computer as it relates to where on the page the user has scrolled. Taken from http://jazz.computer/info

The audiovisual relationship of Jazz.Computer is tightly bound up in its creative interactivity (I take a deeper dive on ‘interactivity’ in web sound art in this other article). However, nuanced audiovisual relationships in web sound art may be just as present in web sound art works that have a more conventional mode of interaction. One example of this is in the polyrhythm, short-form videos by Project JDM.

Perfect Loop

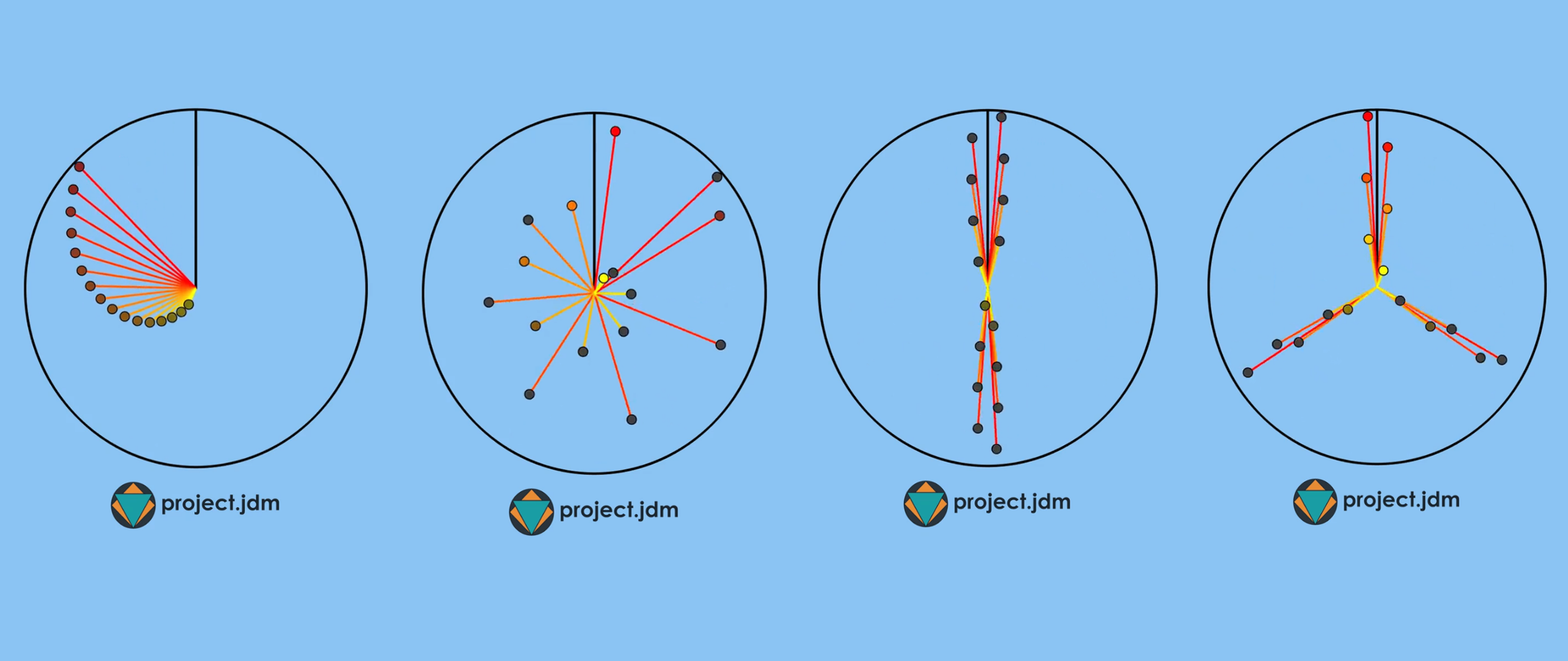

Project JDM is a music content creator largely known for short and long form videos of polyrhythms (here are three examples). What on the surface seem like straightforward audiovisual studies carry in their background a strong curation of drama and narrative. Project JDM’s work is created for video streaming (TikTok, Instagram Reels, and YouTube Shorts, as well as long form videos on YouTube) and typically consists of a complex polyrhythm expressed through looping visuals and sounds. For example, this video consists of 16 pendulums of different speeds bouncing off either side of a single wall (a 12:13:14:15:16:17:18:19:20:21:22:23:24:25:26:27:28 polyrhythm). The video is exactly two minutes long, and within that time the outer pendulum strikes the wall exactly 12 times, the second most outer pendulum exactly 13 times, the third most outer pendulum 14 times… so on and so forth, with the innermost pendulum striking 28 times. Each pendulum’s strike sounds its own pitch, with the pendulums all together sounding three octaves of the scale C, E, F, A, B. Because the count of certain pendulums share common factors (e.g. 12, 20, and 28; 12, 18, and 24; 13, 16, 19, 22, and 25), the flurries of individual pitches in the polyrhythm are punctuated by ever increasing and decreasing occurrences of larger chords (i.e. multiple pendulums striking at the same time)

Four different moments in Project JDM’s pendulum video. At different moments, the pendulums appear as individual agents, while at others they appear as larger combined entities

Especially in comparison with Jazz.Computer, the relationship between audio and visuals in these videos are incredibly straightforward. The entire video is predicated on perfect synchronicity, not just between the visuals and audio, but also how the audio loops, as well as the periodic, metronomic nature of a polyrhythm. Not only that, a single polyrhythm, the very kernel of the content, might be seen not even as enough material to be a compositional work. It may be seen as a math exercise. However, while in some circumstances a simple 1-to-1 synchronicity may sap away tension, play, or dialogue out of audiovisual music, the hyper-synchronicity of Project JDM videos exploit specific rhythmic and melodic progressions that lead to a composed, musically dramatic work.

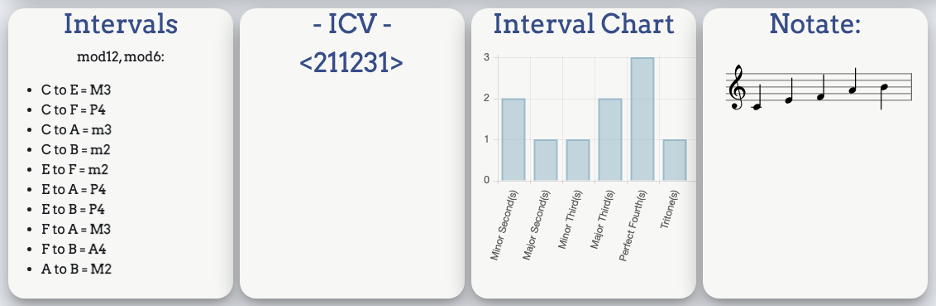

In this 16-voice pendulum video, the pitch set of C, E, F, A, B is a key element of the dramatic trajectory. Examining the pitch set in isolation, this five-note collection is extremely rich in its intervallic content, with an interval class vector of [211231]. To clarify, if you measure the melodic distance from each note to every other note, you will discover that this set contains all of the intervals in the standard 12-tone system. (The [211231] refers to how many of each interval is present: two counts of m2, one count of M2, one count of m2, etc. To provide some context, the major pentatonic scale, a common pitch set with relatively less intervallic richness, has an interval class vector of [032140] (no counts of m2 or tritone). You can read about interval class vectors and other post-tonal theory concepts here). Now, rich intervallic content is nothing noteworthy on its own. However, for Project JDMs complex polyrhythm, where many combinations of the 16 pendulums/pitches are systematically striking as chords, the rich interval content maximizes the contrast between each chord’s timbre. The arrival of these chords, these mini-synchronizations between pendulums carry harmonic momentum.

An analysis of the pendulum video’s pitch set, from Music-theory-practice.com’s interval vector calculator.

The visual of the pendulum also amplifies forward momentum. By order of each pendulum being identical in structure, varying only gradually in velocity, color, and length, the eye of the user easily recognizes and anticipates the coming of each chord, each synchronization of the pendulums. At times, the pendulums all together appear as a single wave. At other times, they are like two waves, or three waves, crashing through each other. Even other times, they are more like a chaotic cloud of random vectors.

As a contrast to this, any human performance of a polyrhythm lacks this systematic kind of visual momentum. In this cover of a Project JDM video, Dan Tramte of Score Follower performs a 1:2:3:4:5:6:7:8:9:10:11:12:13:14:15:16 polyrhythm on the piano, while a sheet music transcription of said polyrhythm scrolls above. This video carries a different form of expression, more akin to virtuosity than to asmr-like synchronicity. While this human performance of the polyrhythm is accurate, the varied, highly individual movement and length of each finger don’t provide the strong visual gestures that are present in the scrolling sheet music above, and other computationally generated animations like it.

Dan Tramte performing a 16-voice polyrhythm on the piano, with scrolling sheet music above.

I described Project JDM’s videos earlier as polyrhythms. And while polyrhythms play a central role in the work, the creative core of the videos is not the polyrhythm itself, but the visual and harmonic choices made to exploit and emphasize the mathematical symmetry in said polyrhythm. Furthermore, Tramte’s take on polyrhythms in his cover video highlight how that rhythmic material can be molded into other creative expressions, like that of virtuosity, or possibly even education (by way of the sheet music in the video).

Towards a Critical View of Audiovisual Relationships

Bringing back Jazz.Computer once more, these two case studies of audiovisual web art take opposite approaches to developing audiovisual drama. In both works, the visuals and audio are highly correlated to each other; neither example is refusing to put the two in a cooperative relationship. However, Mann’s mode of developing that audiovisual premise is through subversion of expectation. The music and visuals shift together at first, but eventually branch into their own independent pathways. The common thread of an engaged, interactive user keeps the two elements working in counterpoint. Project JDM’s pendulums are unwavering in their audiovisual 1-to1-ness, and it is only through that constancy that the rhythmic, melodic, and harmonic drama of the work comes forth so clearly. The relationship between sound and image in web art is often an intentional creative decision. However, that intentionality does not necessitate that good audiovisuals must be complex or subversive. Ultimately, the creative core of the work could lead to either end of that spectrum.

To Top ↑