If we are always interacting with art (that is, listening to it, viewing it, experiencing it), what

is meant when we call something “interactive art”? “Interactive art” is as much an aesthetic inquiry

as it is a technical one. “Interactivity”, as a term, is a core component to the internet’s identity

and architecture. It is through clicks, and posts, and views, and likes, and tags, that we move

through, shape, and experience the internet. Composing these interactions (that is, designing a

webpage, or developing an app) usually has the straightforward goal of creating an elegant, clear,

and uncomplicated user experience. It is a technical task.

However, when a work of art seeks to express something other than a smooth user experience, it is

approaching “interactivity” not just as a technical topic, but also as an ontological one. What

aesthetic significance does an interactive artwork place on the user experience, to merit that label

of being “interactive”? Making “interactive art” means that this otherwise necessary component of

art (viewing it, listening to it, thinking about it) is now being expressed in a different way. It

could even be said that interactive artwork makes commentary on what it means to interact with art.

For this inaugural article for WebSoundArt, I look at three works of interactive art through this

lens. Each of these works approach interactivity differently, not just in its physical, technical

components, but also in how interactivity is defined.

"Click Here"

Making Art Out of Everyday Internet Tools

Screenshot of Holdspace while spacebar is depressed.

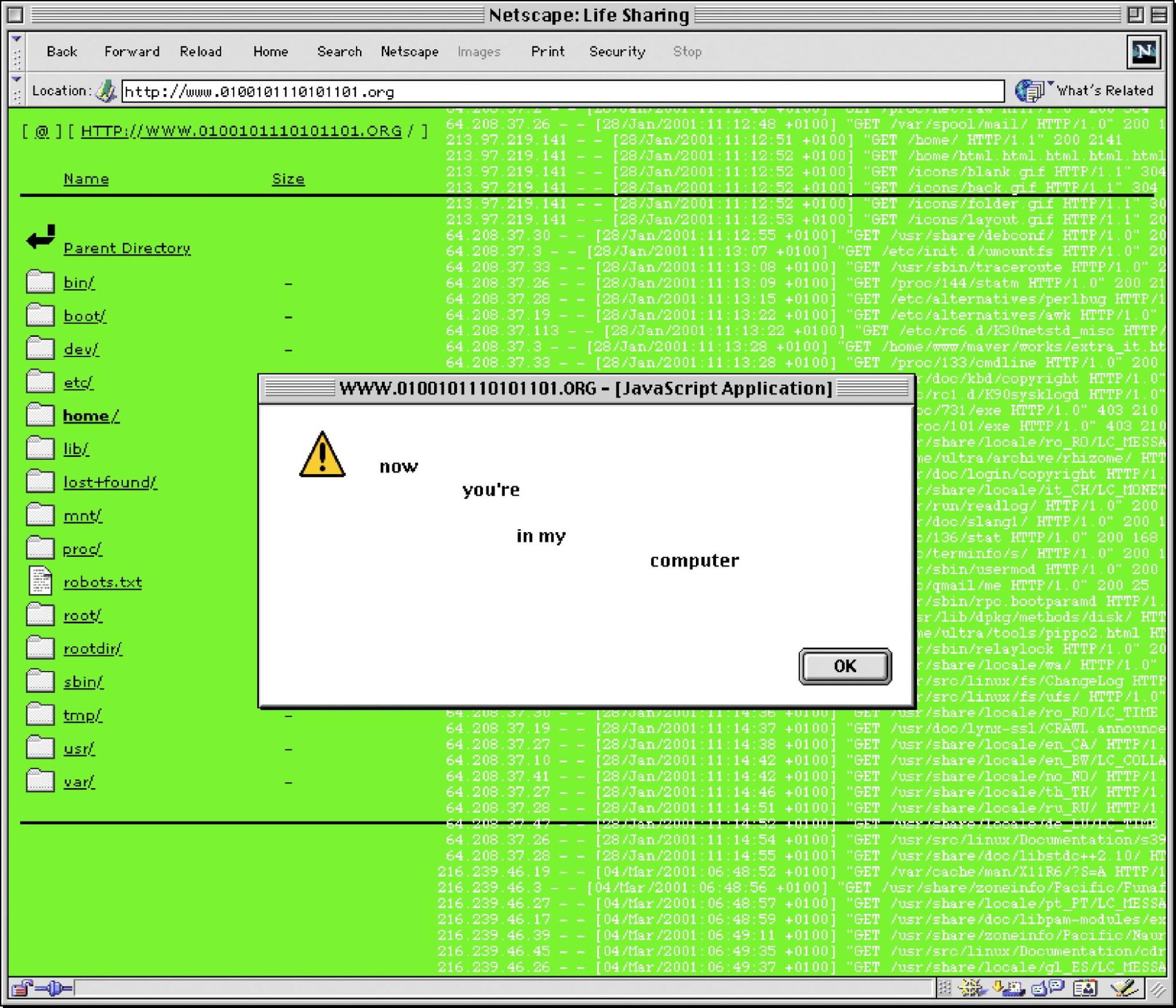

Holdspace is a web page by Carlos Yusim, and it is a kind

of musical etude in using interactive web

elements. Holdspace begins by prompting a user to press the spacebar and then to release it at any

time. When pressing the spacebar, a piece of music with synchronized 3D animations begins to play,

and a progress bar at the top of the window moves slowly forward. When the spacebar is released, the

music and visuals shift in tone, becoming more subdued and quiet, while the progress bar up top

reverses its direction. Press the spacebar again, and the original music returns, continuing from

whatever point in time the progress bar is at. The effect is that the user may move the piece

“forwards” or “backwards” at their will, with both directions triggering a composed audiovisual

sequence.

This piece is elegant and concise. The nature and purpose of the interactive spacebar is immediately

clear. The visuals and audio are sleek and well mixed, and yet they don’t propose anything out of

the ordinary. The sound itself is not interactive in any way - it is a fixed track. Our attention is

drawn to the spacebar, a singular access point to interact with the webpage, to control when and

where these fixed tracks are deployed. Additionally, the music and visuals develop slowly with much

anticipation and tension. The form of the “forward music” is a continuous build in energy, and this

incentivizes a user to curate their own timing for the audiovisual music.

At one level of understanding, there is really nothing to say about what makes this interactive. The

user must very intentionally handle the artwork in a way that is not typical to music. The

simplicity of the spacebar-trigger is a strength of the work. With a very little code, and a

straightforward concept, this work generates a relatively high amount of energy and drama.

The interactivity of this work is also constrained and is contained to a particular aspect of the

art. No matter how you press the spacebar, the sounds and visuals experienced are exactly the same

every time. The interaction is binary; spacebar on, spacebar off. In this next example,

interactivity is not ascribed to a specific parameter of a work. Rather, it is a work composed

around the relationships between artist, art, audience, and collaborator.

"Mouse Clicks Are Not Interactivity"

Interactivity, Power, and Control

Screenshot of Life Sharing home page. Image from Net Art Anthology presented by Rhizome

Since 2000, the artist duo Eva and Franco Mattes have created a series of works about private and public digital life, voyeurism, and transparency involving individuals’ private digital information. The first of these types of works, Life Sharing (2000-2003), is what I will write about in this article. However, I will give a brief overview of three related works to provide a broader context.

- In Life Sharing (2000-2003), Eva and Franco Mattes publicly exhibited their desktop computer, screen contents, files, and browsing history for three years, all available to download and view online (view here).

- The Others (2011) is a two-hour slideshow of 10,000 photos taken from other people’s computers, without their knowledge.

- Riccardo Uncut (2018) is a video slideshow containing photos and videos from a used phone sold to Eva and Franco through an online call. The slideshow contains 3,000 images and videos taken from the phone.

- Hannah Uncut (2021) is a similar video slideshow, containing all the photos and videos on a used phone, sold through an online call. Unlike Riccardo Uncut, this slideshow contains every photo and video on the phone, presented in chronological order, with no edits or further curation.

In notable contrast to Holdspace, the physical actions involved in experiencing these works are no

different than “typical” interactions with installation art. Life Sharing is experienced through an

interactive website. However, there is nothing about the interactive elements on this website that

are anything other than typical.

The interactivity of this web-art has nothing to do with the website, and has all to do with the

voyeurism and exhibitionism that the website facilitates. By making the computer’s personal contents

public without any explicit purpose, direction, or censorship, the audience becomes a performer,

alongside Eva and Franco, in the execution of this work. This work is not the website itself, but

rather the three-year performance, where Eva and Franco exhibit themselves, and the audience view,

handle, download, and interact with them. Like Holdspace, but in a much different context, the work

is interactive by mode of it needing the audience to participate in order for the performance to

occur.

Eva and Franco gave an interview in 2001 (during this work’s performance) in which they spoke

explicitly about interactivity on the web:

“‘Interactivity’ as it is usually meant, is a delusion, pure falsehood. When people reach a site - net.art or not, it doesn't matter - by their mouse clicks they choose one of the routes fixed by the author(s), they only decide what to see before and what after: this is not interactivity. It would be the same as stating that an exhibition in a museum is interactive because you can choose from which room to start, which works seeing before and which ones after…. art in the web can really become ‘interactive’: the public must use it interactively. We must use an artwork in an unpredictable way, one that the author didn't foresee, to rescue it from its normal routine and re-use it in a different and novel way, otherwise all the paradigms of traditional art will impose themselves again.” – “Now You’re In My Computer”, 2001 Interview with Jaka Zeleznikar

For Eva and Franco, interactivity has nothing to do with the technical affordances of the web and all to do with how art is used. In Life Sharing, the act of using manifests in how the internet user handles the information they view and download from Eva and Franco’s computer. Later in the interview, Eva and Franco speak about Life Sharing directly:

“From the moment life_sharing started, every Internet user has free access, twenty-four hours a day to our computer. They can rummage through our archives, search for texts or files they're interested in, check what kind of software we work with, watch the "live" evolution of our projects and even read our private mail. Simulation, intellectual property, production and distribution of culture, the dualism between open and closed are some of the topics that this project wants to question.” – “Now You’re In My Computer”, 2001 Interview with Jaka Zeleznikar

Eva and Franco, in their description of Life Sharing, only list possibilities of how an audience may

behave, but they never highlight any particular decision or scenario over another. To compare this

perspective with Holdspace, a user in the latter work is involved primarily to serve a specific

function (i.e. press the spacebar) prescribed by the artist. In Life Sharing, the user’s involvement

is neither subservient nor elevated above that of Eva and Franco’s. The outcome of Life Sharing is

as much a consequence of the audience’s actions as it is a consequence of those by Eva and

Franco.

Between Holdspace and Life Sharing, interactivity approached as a relationship between user and

artwork, as well as user and artist. In this final example, I will look at a work by composer

Alexander Schubert, which considers the calm and violent dynamics that can exist in an interactive

system.

"Friend Me"

Art Social Media, Social Media Art.

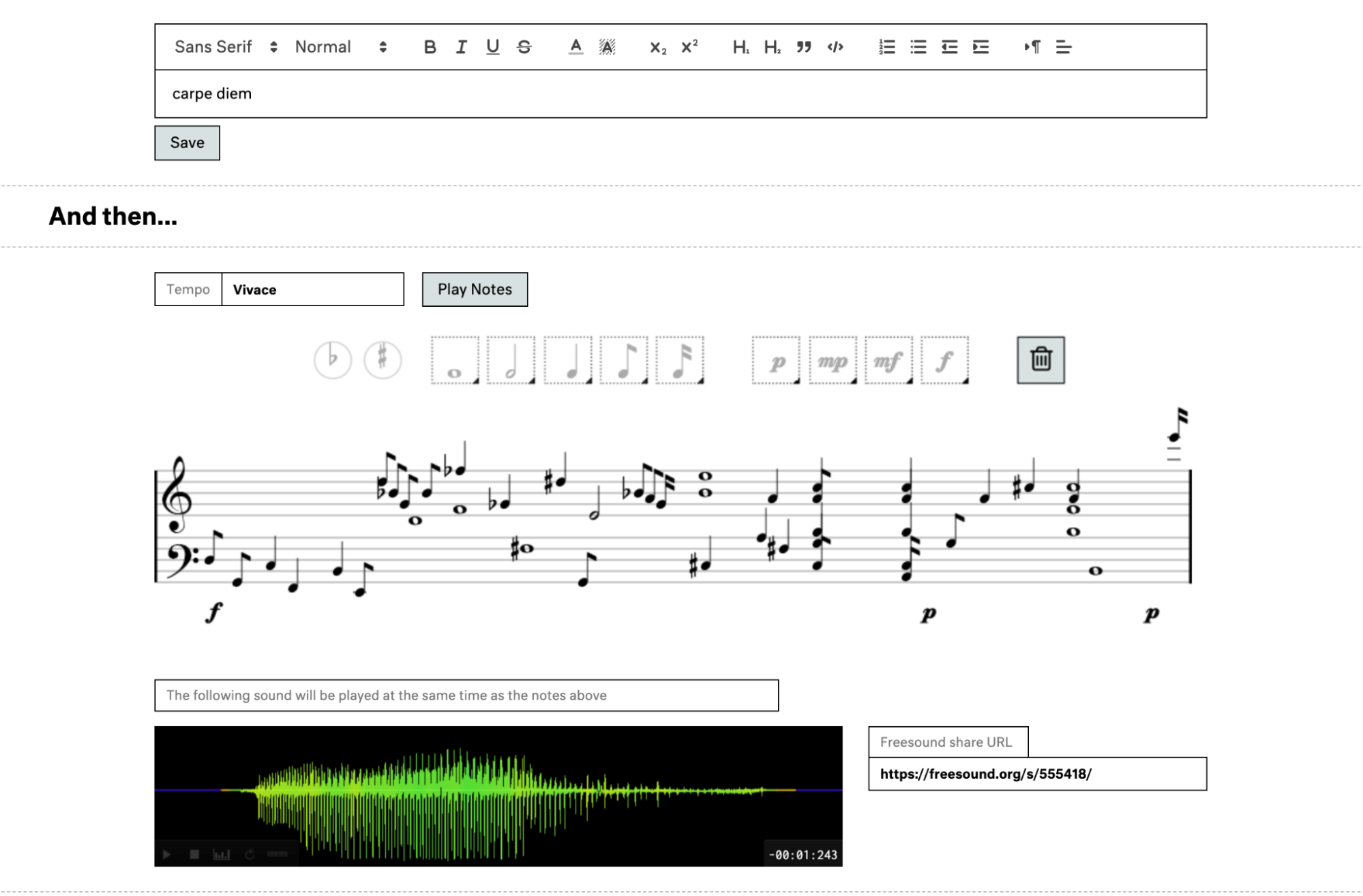

Screenshot of Piano-Wiki.Net editable score from May 4th, 2023

Wiki-Piano.Net is a work for piano and online wiki page.

Described on its site as an

“interactive

community-based piano piece”, the webpage is a score of piano music full of fixed and editable

elements. The editable elements can be changed by the site’s visitors at any time, and the result is

a piano score that is “composed” by a community of people. In addition to the score being online at

all times, this work is performed in concerts by a pianist. The pianist will play the work in

whatever state it is in, and usually the audience of those concerts will edit the work in real-time

during the performance.

Both components of Wiki-Piano.Net (the online site, and the live piano performances) have their own

approaches to interactivity. The online site is similar to Holdspace in a lot of ways. The user is

given a predetermined set of interactive elements to use. And while in Wiki-Piano.Net these elements

are more extensive than Holdspace, both deploy interactivity in a constrained manner in which the

overall identity of the website remains the same through each user edit. The live performances of

this work present a more fluid interactive space.

In comparison to an internet user visiting the site at their leisure, the relationship between

audience and artwork are much more adversarial in the context of a live performance. The website on

its own, detached from the pianist, is a robust interface that retains a particular visual look and

user experience. On the other hand, the performance of the pianist is very much at the whim of the

audience's behavior, as they edit the score in real time. While in Life Sharing, the agency between

the Internet User and Eva & Franco is relatively even, the balance of power between Piano-Wiki.Net

and the audience is much more violent. In the live situation, the audience hijacks the work, while

outside of the concert, the work retains a kind of austere robustness. Another way of seeing this is

that the webpage is resilient to a community attack, while the human pianist is not.

This trio of webpage, pianist, and community audience also introduces a level of self reflexivity

when it comes to what aspects of the art are “interactive” or not. The work’s statement on the

website, that it is an “interactive community-based piano piece” speaks not just to the novel

interaction between the community and the website, but also the conventional interaction between a

pianist and a musical score. These two layers are made more apparent by the difference in

adversarial energy between score/webpage and pianist, and between score/webpage and audience.

When a work of art is named as “interactive”, it makes both technical and ontological statements about what it means to interact with art. The works examined in this article demonstrate different ways of achieving interactivity, particularly in the context of web sound art. From using a simple trigger to control an audiovisual sequence in Holdspace, to the interplay of voyeurism and exhibitionism in Life Sharing, to the multiple layers of conventional, experimental, online, and live-in-person interaction in Piano-Wiki.Net, interactive art expands the possibilities of how art can be experienced and understood, and it highlights the presence of the relationship between the artist, the art, and the audience.

To Top ↑