Between promises, critiques, and memes, NFTs (non fungible tokens) have been, in the eyes of some, a technological and financial revolution. Yet to others they are just another bubble of financial speculation. The artist economy, like many others influenced by trends in tech, has its very own set of hopes and doubts towards this technology. New business models and niche crypto communities claim that blockchain technology brings solutions to a fraught and fragmented artist economy. In particular, NFTs propose a solution to the opaque and fragmented reality of music royalties. Additionally, they propose to artists new streams of income, a bold claim to come in an era where music’s increasing digitalization moves hand in hand with its difficulty to make money. But how legit are these proposed promises? In this article, we will take a look at the particular problems of music royalties, examine how NFTs propose solutions to them, and determine to what degree those solutions meet expectations.

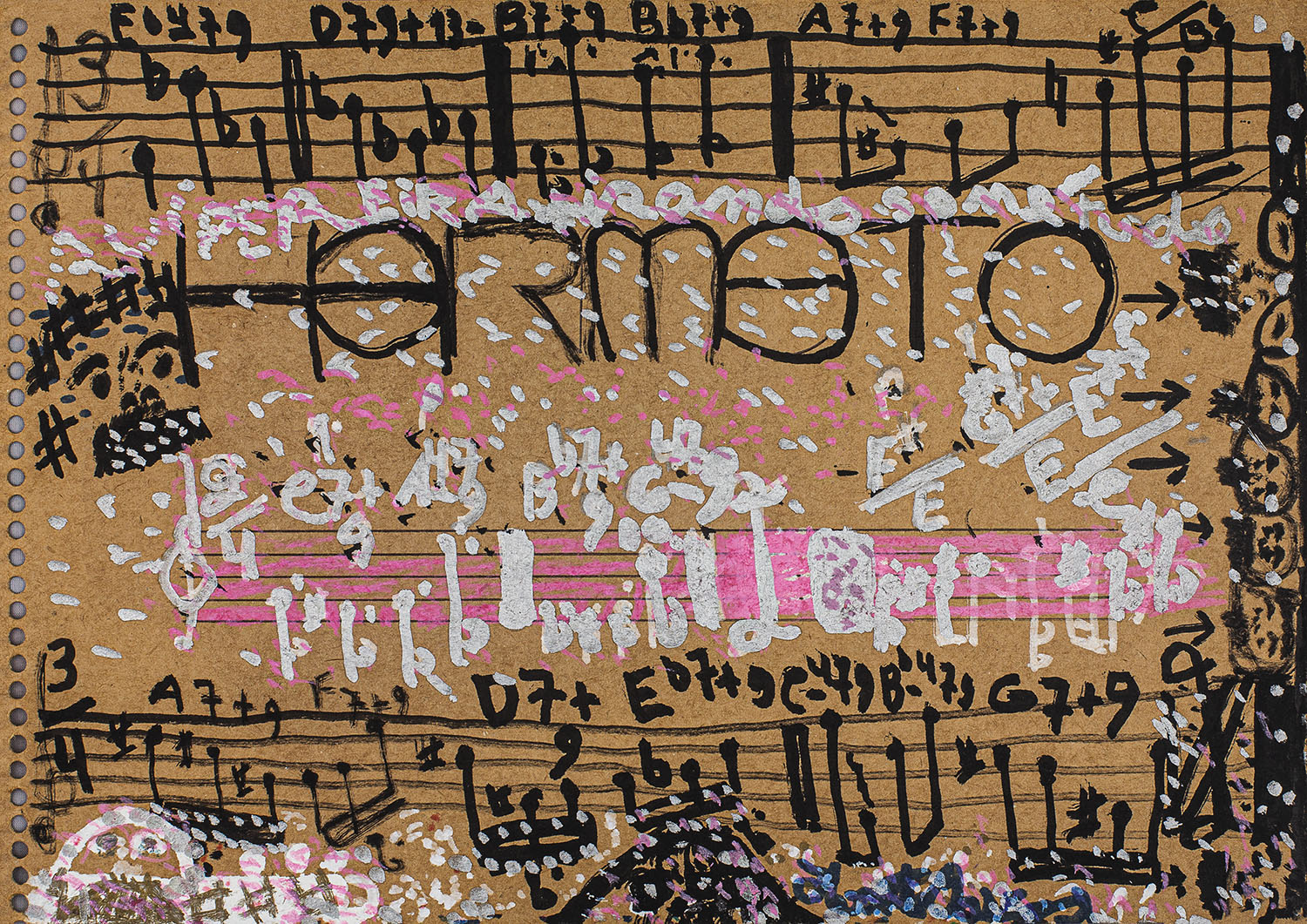

Só não toca quem não quer, a physical book of sheet music + NFT by Hermeto Pascoal. This NFT functions as a mechanical license to record the music to an album.

The Problematic State of Music Royalties

For most artists, receiving royalty payments is a slow and complex process. The inner workings of royalty collection are clear on paper, but opaque in their implementation. Oftentimes it is the artists (rather than streaming services, or collection agencies) left at a financial detriment. In order to understand a blockchain solution, we must first explore the present problems.

Royalties are payments made to an artist by a third party, as compensation for using the artist’s work in some form. Because music can be used in many different forms (streaming, film and television, traditional radio, satellite radio, printed sheet music, social media content, advertisements, and live covers, to name just a few), there are many different types of royalties. Mechanical royalties are payments from streaming platforms, CD sales, and song downloads; Performance royalties are paid to songwriters, arrangers, and others who benefit from a piece of a live performance or broadcast of music; non-interactive royalties are for satellite radio, print royalties for sheet music publishers, synchronization royalties for use in commercials and television; each of these formats are valued differently (1 stream on Spotify is less valuable than 1 spot in a Netflix series), and thus each have their own type of royalty, oftentimes collected each by different mediating organizations (e.g. ASCAP, BMI, SESAC, GEMA (in Germany), MLC, DLC, SoundExchange, and other acronyms…)

This presence of a mediating body, between the third party and the artist, is a necessary evil. Third parties cannot simply be trusted to give money directly to artists, and artists would have no bandwidth or infrastructure to seek out all the places their music might crop up. This all doesn’t even mention how the revenue of a single piece of music is often split between dozens of artists, songwriters, producers, agents, labels, distributors, and other stakeholders. Thus, these mediating organizations come in to verify, collect, and distribute royalty payments. In 1790, this system was simple enough, as all copyrighted music was defined as lyrics or sheet music authored by one person. But with every technological innovation that took over music distribution, and with the growing nuance that our discourse around authorship has taken, additional sets of laws and royalty processes are created, and an additional mediating body is formed to verify, collect, and distribute those royalties.

For artists, there are three major issues with this system: clarity, speed, and trust. The fact that these many moving parts are difficult for anyone to understand is self-explanatory. However, the reality of this comes at the detriment of artists’ finances. In 2019 it was estimated that there were $2.5 billion (around €2.73 billion, red.) in royalty payments collected from streaming services, but had not reached the hands of artists. While streaming companies, advertising agencies, and these mediating royalty collection organizations are full of employees educated in copyright law, many artists must learn for themselves how to register and navigate their relationships with these organizations. It’s no wonder that money has a hard time reaching its end destination. The process of verification, collection, and distribution is also slow. Royalty payouts can often take months, even years, to get to an artist, making them a further unreliable source of income for musicians.

This third issue, trust, is not what you might expect. These organizations are, by most reasonable measures, trustworthy. They are non-profits designed specifically and solely to create trustworthy royalty transactions. It is actually not a question of mistrust that is the core problem, but rather it is the method of establishing trust between parties in a royalty payment.

La Hora is a series of 25 NFTs that grant the owner access to shows and merchandise by the artist Ohgaitnas. Purchase of these NFTs also trigger a 10% royalty payout to the author.

Smart Contracts and Trust

Smart contracts are a core component of blockchain technology, one that some have heralded as a solution to the music royalty problem. At its core, a smart contract is a digital script of code that is triggered by a predefined action that occurs on a blockchain ledger. NFT (non-fungible tokens) ownership is a common example of this. When an NFT is minted, the blockchain it sits on triggers a smart contract that assigns ownership to the author. When the author sells or transfers ownership of the NFT to another, a smart contract lists that transaction on the blockchain. A smart contract is a process that is not only automatic, but it is also publicly observable. These two qualities are the essence of a possible royalty payment solution. Through automation, a royalty payout can be faster. Through a public blockchain, the royalty process can be trustworthy and auditable.

To illustrate an example of a smart contract-triggered royalty: a license to use a piece of music could be purchased as an NFT, and through a smart contract, this purchase would automatically trigger a royalty payout to the artist. A key difference between this scenario and that of a royalty collection agency is the locus of trust. In the smart contract scenario, this royalty payment is public, observable and auditable by anyone on the blockchain (to use a keyword thrown around a lot in crypto circles, it is “decentralized”). Trust is generated from openness, whereas in the context of conventional music royalties, trust is maintained by the integrity of the collection agencies (it is “centralized”). The enormous effort involved in creating and maintaining the collection agencies can be bypassed. And in turn, the royalty payment would occur much more quickly as well.

NFT royalties already exist in niche crypto communities and markets, but have yet to occur in a widespread manner. The exact terms of a royalty payment is specific to every NFT. Unlike current royalty payout processes (which are shaped by copyright law), NFT royalties do not have any standard form. The author of the NFT often sets their own terms for the purchase and use of their work. For example, Hermeto Pascoal sells NFTs of his sheet music, authorizing a buyer to record a performance for an album, but does not authorize the music to be used in advertisements or audiovisual media (I found this case study in a fascinating report on Music NFTs in Latin America by Water & Music). One could imagine a system for streaming services where each stream of a song triggers a smart contract (written either by an artist, their label, or a distribution service like DistroKid) and a royalty payout directly to the artist. At the end of the day, smart contracts are algorithms written by humans, and can be whatever the author wants them to be.

Metadata and Compliance

So does this solve the problem of music royalties? Not quite. While smart contracts address problems of speed and trust, they do not provide a clear solution for the lack of clarity in music royalties. Specifically, accurate metadata is essential for a royalty process to occur. Imagine a film production uses a song in the closing credits of their movie. It is information about the song, such as the names and other identifying data of the artist, which makes it possible for a collection agency to connect that use of the music with the specific artists who made it. Now while it is likely that a professional film production has the correct information about the song they used, there are many other scenarios where this is not the case. For example, YouTube videos and other social media content is often created by users who will not mention or credit (let alone, pay a royalty) music that they use in their content. The lack of metadata in a YouTube video’s background music can’t be solved by a smart contract or NFT. Additionally, there are malicious actors who will upload music that does not belong to them, but label the metadata such that it appears to credit them and not the artist. It is also the job of these platforms not only to label metadata accurately, but also to correct and regulate inaccurate metadata. Blockchain technology on its own has no solution to this, and the larger a royalty system grows, the more bad actors appear.

Instead, streaming and social media platforms rely on music information retrieval algorithms and other AI technology that can sweep for music and label it with accurate metadata. It is likely that a blockchain solution to music royalties would bring incremental improvements, only in tandem with many other systems and technologies in place.

Finally, related not to music, but rather to blockchain as a whole is an unanswered question of regulation and compliance. Smart contracts, in fact, are not legal contracts. They are just digital code. The “laws of blockchain” at this moment are local to a given ledger or NFT marketplace. But for blockchain and cryptocurrency to take on the weight of the entire music royalty system would require a much more universal system for defining and enforcing these systems. (Nadia Eghbal has an interesting take on rules and governance in open source communities in her book Working in Public from Stripe Press. She draws connections between open source software development and Elinor Ostrom’s theory of the commons. While she doesn’t speak specifically about blockchain, the open-source premise of web3 technologies like it could also be evaluated against Ostrom’s research).

Will NFTs help artists make royalty money? For those interested in diving deep into the NFT music space (for starters, here, here, and here, there is a lot of control over the terms of an NFTs royalty payments. However, the technologies latent in blockchain are not overhauling the music royalty system as we know it. In the future though, it is likely we will see some sort of smart contract technology paired with many other initiatives and technologies to make incremental improvements to music royalties. Smart contracts offer a remedy to slowness, by automating and publicly recording royalty transactions. This public, decentralized, system also bypasses the need for a royalty collection organization, instilling trust transparency. However, metadata accuracy is a central component to music royalties that blockchain itself is not poised to address. Additionally, if a blockchain system extends to a larger share of the royalty payment ecosystem, the need for a universally accepted set of legal regulations becomes more necessary. The problems and solutions of music royalties are nothing new to the artist economy. Blockchain technology is an important tool that will need to work with many other current and developing solutions in order to create a better system.

To Top ↑