Vanilla with a scoop of humour: An unpatented journey through Sebastian Adams’ kaleidoscopic practice.

My third interview partner is Sebastian Adams, a composer and viola player from Ireland. At the time of the interview, he was in the middle of moving back to Dublin after spending two years at the IRCAM in Paris. As you will notice, Sebastian is a very prolific artist with many interests beyond creating web sound art. “I’ve always had a quite scatterbrained approach. I get interested in a lot of different things, and so I have work that touches on a lot of different disciplines. It kind of seems like it comes from different backgrounds as well.” This is reflected well on his website: not only can you see the diverse topics he is currently thinking about, his worklist shows a broad range of works, varying from orchestral pieces and piano trios to Twitch-based chat music, installations, and snippets of code testing various ideas.

We talked about topics varying from composing and coding to copyright and forking—and that is just the part that made the cut. What goes on in this person’s mind? Apparently, loads of things! Where did these originate from?

Sebastian Adams: Well, I come from a musical family. I played viola as a child, but I didn’t take it very seriously, so my level was quite low. And I was a choirboy. So I had quite a high level of musicianship; I could sing, had a good ear, and stuff like that. Then, I studied composition. Luckily there was a very good composition undergraduate degree in Dublin, where I got a lot of personal attention from the teachers because it had extremely small class sizes. Viola was a second study. Because my level was pretty low, but not zero, I was able to play with people who are a lot better than me, which helped raise my level a bit. I don’t play really notated music anymore — [jokingly] because I still don’t practise — so I’ve been much more of an improvisation specialist. And I love playing. I still play a lot, but I rarely play very strictly notated music.

One of the main things that has defined me as an artist has been that, when I was about 20, I started an ensemble, Kirkos. Very quickly, I was spending as much time curating and producing concerts as I was composing. My work followed the trajectory of what the ensemble was doing in many ways. We started off as a more traditional instrumental contemporary music ensemble, and then gradually, we became interested in things like Fluxus and picking up the ideas that were going around in Ireland in general. We would be trying to test the temperature of what other people were doing in Ireland and programming based on what the artists around us were interested in. I suppose that’s probably part of why I ended up being a little bit like a magpie myself, because I was being exposed to a lot of different influences all the time and trying not to be too rigid in my tastes. So, my music kind of drifted to being more experimental and less traditionally scored over about 10 years, until the point where now I rarely use scores.

And then I always had a background interest in computers and using computers for music. I was one of those children who find the idea of computers romantic and amazing. I never really had the opportunity to learn how to code when I was a child, but I was always sort of messing with the computer. So then, I was also doing electronic music production a little bit as a teenager. And funnily, even though I had a classical background, my first step into writing music was through things like Reason and FruityLoops.

JDT: And how did you get into coding?

SA: When I was still only 18 or 19, I wrote an algorithmic piece. It was just a small string quartet, which was completely pizzicato, and it was based on some kind of rules. I remember it was a lot of manual work. When I finished the piece, I had to come up with a smart way of inputting it quickly, and I used Cubase because I realised that would be quicker than writing it in Sibelius. And then, when I finished the piece, I realised it was boring because, basically, the parameters weren’t right and I would have had to redo it from scratch to change them. So from that moment on, I was like, “Okay, well, I’m never doing something like that again by hand. If I ever want to do a piece like that, I need to learn how to programme it.” A couple of years later, I did an Erasmus in Vienna in the electroacoustic department at MDW. That was a really great place to go if you had that kind of interest, because they’re doing computer-aided composition there. So I remade that piece in one of the classes with Johannes Kretz. Patchwork I think we used. He also introduced me to the Bach library for Max/MSP, which I think had only been released about that year. I think people were beginning to think of the potential of computers to do this stuff. So it was probably the early experiments in that, or at least in making it a bit easier to use for people who weren’t like computer scientists. And so, I started playing a lot with that. This may have started in 2013. So after spending a long time with that, suddenly I had a good level of Max. It started to rewire my brain a bit to work in more of a computer programming way. The transition to using code rather than working in Max came a bit later, for a very pragmatic reason. I wanted my website to have, like, a searchable or filterable list of my pieces. I must have had nothing to do at the time because I remember it taking me weeks and weeks, but I figured out how to do that with JavaScript. By the time I had done that, I had learned how to use JavaScript. And then, you know, every time a project came up after that where I thought, “Hey, maybe I can actually do a bit of coding for this,” I would be able to try and do it. And so I gradually became more fluent.

© Daryl Feehely

JDT: Do you feel like there is a difference in your way of working, in your mindset, when you’re writing pieces to be performed on stage compared to when you’re coding web sound art, which is probably more one-on-one?

SA: I do. Definitely. Normally, when you’re writing a piece of music, it’s designed to be listened to in a communal setting. Whereas the one-on-one aspect of using a website is a very private exploration. The user has so much agency in an interactive web environment. I try to think of it as being much less controlled. To be honest, this has shifted my perspective on writing music anyway. A lot of the music I write now is about giving up some control in different ways. I don’t know if the impetus for changing my work in that way somehow was related to me working with web stuff as well, but it’s less about designing the perfect piece of music and more about making something that’s interesting and where the user finds something out or enjoys themselves as they explore more.

JDT: Then, according to you, where lies the difference between web-based sound art and composition?

SA: I don’t know if this is a cop-out, but I sometimes feel like, as artists, we don’t necessarily need to be the people who answer that question. I normally explore an idea because I have an interest in it. And, if I think about it at all, I try to figure out what discipline or genre it is later on. I don’t worry too much about whether I even know what kind of genre it is. But it is obviously important to know how and where to present it. I suppose questions of genre and discipline are very, very important for that. So that’s why it’s maybe a cop-out not to care about it, because then you can go, “Okay, well, does this belong in an exhibition? Does it fit in a concert? Is it just out there, and nobody’s ever going to find it because they don’t know what box it fits in?”

JDT: I feel like if you want to build a community or connect the people in the community more, you have to somehow create the space to show this. What do you think about this?

SA: It’s something I’ve been thinking of, particularly in the last few months. I had a really good group lesson with the composer Matthew Shlomowitz. The question that Shlomowitz had for us was like, “This is all great work. But the problem is, I don’t understand where it goes. And so I don’t understand how people will find it.” I realised I didn’t have a good answer for that. You have a beautiful idea and you spend a long time making it, and then you upload it to GitHub or whatever way you’re getting it out there, and then you leave it, and because there’s such a saturation of media everywhere for all the people who might be interested in that, obviously they’re just not going to ever find it. One alternative I know of is to present it in an art gallery. It gets it to people, so that’s a good thing, but it almost seems like misrepresenting the piece because—especially if it’s something that relies on interaction and it’s designed more with this one-on-one kind of immersion in mind— then bringing it into a public space like that just sort of dilutes that aspect of it. What I’ve done a good bit is tie in websites with pieces that are being played in concerts. You have a guaranteed audience (you hope you have an audience), and you could just tell them that there is also a website that is part of the piece. And then maybe some of the audience will go on to the website.

I’d say probably things like this are very important for web sound art, because then it becomes like a hub where people who are interested in the medium can find other work. I guess in the end, the best way to present it is in somebody’s web browser, on their own device, wherever they want, and so it’s much more about libraries and networks than it is about space. We’re not reliant on a space, obviously, which is a beautiful thing, but it also means that it can be hard to find the work.

JDT: What actually drew you to making web-based sound art?

SA: This is one of the rare times where I started doing something, partly because I really felt like there was a specific advantage to it. I felt that it has this amazing opportunity of removing barriers of access. People don’t have to come to a concert. They can do it in their own house, they can do it on the bus, things like that. Also, if it’s well designed, you don’t need to be tech-savvy to use it. You can be a very normal person who doesn’t care about complex technology, and you can still use these amazing, complicated ideas that artists have put together. Which, for me, is wonderful. I went to a lot of concerts that had sort of interactive stuff. And it would be like, “Well, the audience has to install an app, or they have to log into this specific Wi-Fi network.” And then you look around, and everybody’s perplexed because half the audience doesn’t know how to install an app. I think now we can remove loads of those obstacles. Using the web is this amazing opportunity for artists to go, “Okay, well, I can take all of the technical burden on my shoulders as the artist or the developer and give the audience something that is so easy to use that they can just think about the work and the experience rather than how to use it.” So I love that.

Somebody who used to do marketing for one of my groups told me that with every extra click you add, you lose half your audience on the internet. And I mean, that probably makes sense outside the Internet too. People have so many demands on our attention, and I think as artists, we have to be very mindful of the kind of price their attention is. And so anytime we’re imposing an obstacle, anything we do that puts the piece one step further away from the audience, we should expect that most people aren’t going to continue paying attention because they probably have better things to do.

JDT: We haven’t spoken about your pieces yet. People who read the interview might have checked your work before, might know it, or might check them out after. So could you tell me which of your works you consider to be web sound art?

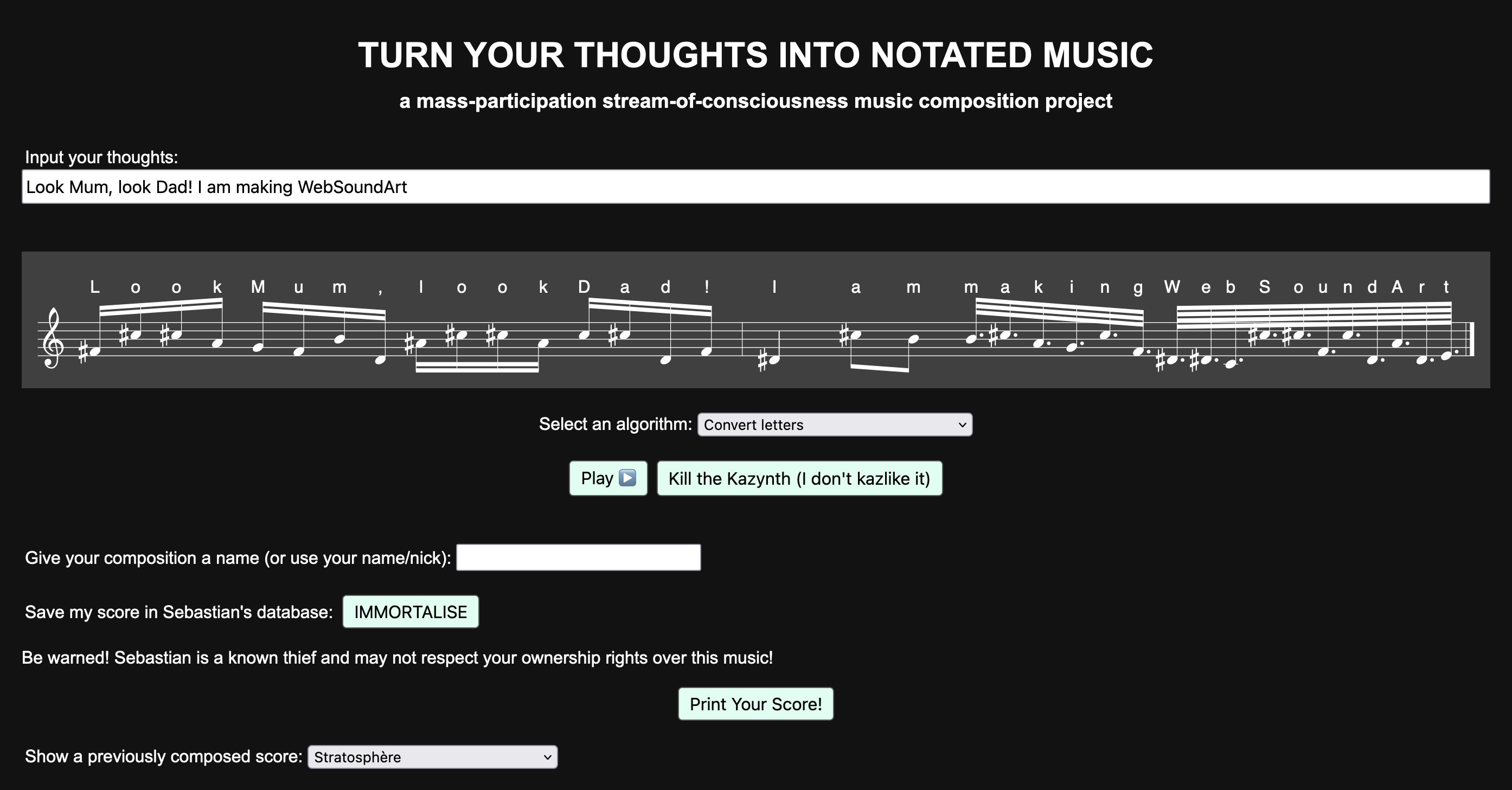

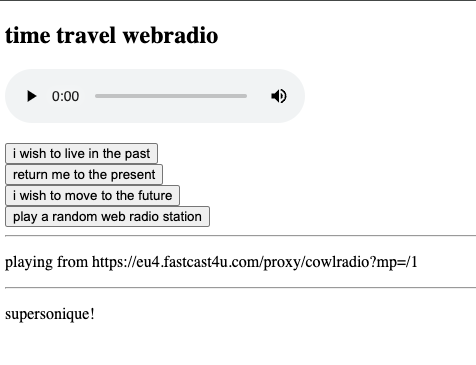

SA: For sure, the little radio projects and the free sound thing. What else, though? I don’t know if you saw my Thought Music, which converts your text into music. I suppose that’s web sound art, but I probably wouldn’t really think about it that way. A lot of the stuff that I have that’s on the internet is probably some other genre. The rest of the Stolen Music project, for example. Even though it’s a big project with a big website attached to it, a lot of it isn’t sound at all, and a lot of the sound is fixed media.

Thought Music

JDT: Stolen Music was your IRCAM project, right? So the piece consists of sections working with the other music programmed in the concert?

SA: Yes, that project started out with lots of Max patches and basically finding out what my colleagues in my class were going to do in their pieces and which bits would make sense to steal. And then I built the website later. But I find that since then, loads of the projects I’m doing are about stealing found material, and in particular, sort of making use of information that’s already out there. I have since then done other things that are kind of related to stolen music and dealing with sound on the web. For example, just the other day I started working on a new idea, which is like a graphic score based on YouTube videos. So, of course, that’s also connected with stolen music. I need to find a way to integrate all of these ideas that are sort of related to that piece into the same website. I feel like that project is still really in progress. It just needs a lot of time.

JDT: This project is about copyright, right? Is there something specific you want to say with this, or are you mainly exploring the idea?

SA: With Stolen Music? Yes, I think I have an agenda there, for sure. Which is that I think we really should rethink the attitudes we have towards ownership of intellectual property. Because, already as an artist, I’ve been on the wrong side of this so many times, personally, where something I wanted to do was not possible officially because of whoever owns the rights to the material we wanted to use. Personally, I think we give far too many rights to people over that stuff. So, I guess I’m trying to be quite provocative with it in my work. Of course, maybe the real answer is something more subtle. It’s a big topic, of course, and I’m not the first person at all to look at it. I got really interested in it after I got sued by a German lawyer for taking a photo without permission. I got kind of radicalised. And then I read this great book, which was called Copy this book. It’s written by a lawyer, and it’s from an EU perspective. It’s quite useful because, for a lot of this information, it is much easier to find the US kind of attitude, and of course their laws are different. I think the laws are different in every country, but in the EU, they’re much more broadly similar.

JDT: So, in an ideal world, can we just copy whatever we want from everyone?

SA: I don’t know about an ideal world, but I would be much more comfortable if we were able to steal a lot more than we can and freely use other people’s ideas more than we can. I think the whole attitude we have towards whether our work is original is so individualistic, and it treats art that’s already been made as if it belongs to one person instead of to the public. I think this doesn’t actually make sense. And so, the more serious point away from the provocative way I present it, which is supposed to be kind of funny and over the top, is really about rethinking this totally individualistic approach to how we distribute ownership, or how we think about ownership. Even people who aren’t directly stealing material to a greater or lesser extent are influenced by the people they know, by famous composers, by their friends, by someone. Many of my best ideas were really almost suggested by somebody else. Sometimes just as a joke, and you go, “Oh, no, that’s not a joke. That’s actually a great idea. I’m going to put that in my next piece.” I didn’t even come up with that. All I did was that I was the one who thought of putting it in my piece. Actually, somebody else has said this. That’s kind of a tangent.

But also, we have so many types of music and art, where the work can’t be made except with many people. And then we give all the credit to one person, like, for example, in contemporary music. It’s very common in instrumental music for specialist performers to meet with a composer and for an hour to two show them everything they can do. They have spent years practising techniques that maybe nobody else or only a handful of people can play. The composer will take notes, write them down, and then just write down this performance specialist technique in their piece, and it will sound amazing. And at the end, the name at the top is the name of the composer, even though what they’ve done is appropriate the practice of the performer and put their name on top of it. And because we have this kind of individualistic way of giving out credit, there are a lot of thefts happening all the time that we don’t notice because we expect a piece to have one composer, and we expect a film to have one director. And so the people at the top of this chain are constantly getting credit for other people’s work, in my opinion. And in so many ways, I think we need to rethink that.

JDT: In this regard, we can learn something from the computer world, where people commonly build on top of each other’s code. Maybe this could inspire artists to be more in solidarity.

SA: Yeah, that would be so cool. Actually, something I was thinking of doing is putting licences like an open source licence basically on my instrumental music—just almost as a stunt because I think if someone wanted to copy my ideas, they would do it anyway. Because, you know, everyone is doing that all the time. We act like you can’t do it.

Radio Time Travel

JDT: Which brings me to my next question: What libraries do you use for your coded projects?

SA: I actually almost exclusively use vanilla JavaScript, and obviously, the Web Audio API. And then I do use external APIs when they’re relevant to the projects, for example, the Free Sound one or the YouTube Data API. I do use P5 sometimes. Not that much, but I’ll probably keep using that because, for the visual stuff, I think it’s too hard without a library. I’ve tried a couple of audio libraries, and I always find that after an hour or two, I may as well do it in Web Audio, where at least I know everything that works is possible. I feel like probably a lot of people are using libraries, and it’s probably smarter to do that. You’re working at a slightly higher level, which is nice. But I haven’t found one that I like.

Because I’m not a programmer by training, I still rely on StackOverflow a lot and on looking things up. Quite often, when I start a project, the first thing I’ll do is just do 10 or 20 different Google searches, open 100 tabs, and see what other approaches people have taken to similar problems. And so I find that using vanilla JavaScript is pretty important there. If I were using something specific, like tone.js for example, I feel like I wouldn’t find many examples of code that I could start tweaking. I still find this is a very good starting point for just getting something that works and kind of learning it that way rather than just reading the documentation. So yeah, for that reason I like to be working with something that’s as compatible as possible with what other people are doing.

JDT: Do you have any tips for aspiring web sound artists?

SA: A web browser is becoming so powerful now. So for people who aren’t already, basically expect more and more things to be possible. Because I think when I got interested in this, a lot of things that weren’t really feasible are now feasible, and I haven’t been doing it for very long. It seems like almost everything will be possible soon. Anything. I mean, I think we’re still at the point where it makes a lot more sense to use Max for a lot of things. But probably that won’t be true for that much longer. So that’s very exciting and maybe not obvious to people who aren’t really nerdy.

JDT: I only have one question left: What does the future bring? Is there anything that is coming up in the next few weeks for you?

SA: My group just did a collaboratively composed piece that was an hour long, called Beginner’s Guide to Slow Travel. We played it in Huddersfield. Part of that we made into a website. The website consists of stuff connected to the piece we made. For example, there’s a slow travel diary, which is… a diary. The concept of the website is that every time you click on a link, a video interrupts it, and the duration of the interruption gets longer and longer each time you click on a page, so it actually slows down your usage of the website. And so it connects with the ideas of the piece.

Otherwise, I am kind of always working on stuff that is related to web sound art, but it’s very hard for me to tell whether stuff will end up in a piece that is public. I throw everything up on my GitHub, but it’s not necessarily linked anywhere. So if someone wanted to do really heavy detective work, they could probably find some of these pieces.

JDT: Challenge accepted…

Some resources

Sebastian Adams’ website Stolen Music Thought Music Sebastian’s coded projects

Kirkos Beginner’s guide to slow travel

To Top ↑