The Memory Palace of Sander Saarmets

A minimalist setting. Black. A single white rectangle is nervously waiting for me on the lower half of the screen. I click on it, and it abruptly vanishes. This turns out to be the start of a path through tetris-like landscapes and dreamy soundscapes. It feels like I stepped into a web poetry session where texts, sound, and code melt together into one cohesive work of art.

The piece is from the hand of the Estonian electronic musician, sound designer, and composer Sander Saarmets. Saarmets is very prolific in various directions. He has written music for ensembles, films, and contemporary dance productions; additionally, he often roams the stage himself with a modular synth set or as his electronic alter ego V4R1; he is part of the Estonian Electronic Electronic Music Society and curates a bimonthly radio show on Estonian national radio. Just recently, his piece and the sky turned yellow was selected as one of the recommended works at the [69th International Rostrum of Composers] (https://rostrumplus.net/2023/05/19/69th-international-rostrum-of-composer-selection-announced/) in The Hague (Netherlands).

Enough praise for now; let’s make things concrete. Before you continue reading, I recommend you visit his two web installations Kipatauw and *Unusta|Forget*. We will be talking about them and Saarmets’ take on WebSoundArt, so this could give you some background on where we are coming from.

For non-Estonian speakers: Don’t get tricked like I did. In the beginning of *Unusta|Forget, click on *Forget to get to the English version. Going through the Estonian version was very interesting to get lost in, but I still recommend you check out a version in a language you understand. Enjoy!

Screenshot of Kipatauw

JDT: Let’s talk about what you call on your website your two web installations, Kipatauw (2020) and Unusta|Forget (2022). What are they about?

SS: They are both about trying to tell stories in a somewhat interactive manner on the web

platform.

The first one, Kipatauw, was born out of the COVID lockdown and out of trying to find

new

ways to communicate art through the web. For me, this work is a bit like audiovisual poetry

because

the narrative can be pretty abstract and the musical form is not so fixed. So everything is more

up

in the air.

The second piece, Unusta, was commissioned by elektron.art. This platform is very much involved in online

forms of art. In this piece, the story is much more in focus, but it is still kind of abstract.

I

got to work with my favourite Estonian writer, Jan Kaus, which was very cool. He really got into

this way of thinking about text in layers and how not everything should appear on one page.

There is

a different rhythm. I also think the way the text appears in short fragments is a bit musical.

You

can grasp bits and then choose when you’re ready to move on, which is almost like interacting

with

it.

JDT: So Unusta is not based on a preexisting text; you collaborated with the person who wrote the words?

SS: Yes, yes, it was really written specifically for this and with the style of Kipatauw in mind. We were discussing with the writer how certain situations might feel. We thought about what would happen if you forgot your language. How would it sound? And then also about the positive aspects of forgetting, because sometimes it can be healing to forget. But you cannot forget without going through things again somehow. If you just block out something, it can reappear at any time. You have to process things and knowingly forget.

Did you get that there are three different stories and three different colours in the beginning?

JDT: Wow, that must be quite the construction!

SS: I had some trouble keeping it small enough for the web, but managed in the end. You know that there are some weird limitations with Node.js. After some point, the sound engine starts to act up. At first, it distorts the sound, then it disappears altogether. I haven’t figured out why or how this exactly happens. I tried to shut down every process the moment it was finished. But still, somehow some limit was reached. It’s nice to try to come up with solutions to these issues that ultimately limit the length of the experience.

JDT: Can you estimate how long it takes to go through the stories?

SS: Well, it depends on how fast you click through the story. You have to time it yourself. I… forgot ;)

Screenshot of Unusta

JDT: Just a very practical question. On which server are they running? They are hosted on your website, right?

SS: Yes, everything runs from the server where the website is hosted. Also, while I was programming Unusta, there was an update on Node.js. The new version didn’t want to work with my old code. I didn’t want to change everything, so I downloaded the previous version of Node.js and put this library on my server so that it wouldn’t change. Because in the usual way, you would have a link to the current version of the library. If you want to be safe, pick the version you want and put it somewhere.

JDT: While I was checking out Unusta, I felt like the content of the text was also very present in the way that the rest of the installation was proceeding, e. g. with the colours, the sound, the blurriness, etcetera. In which way does the content of the text reflect in the code? Is it something you’re doing on purpose, or do you leave this interpretation up to the visitor?

SS: Ah, yeah, of course, it’s all very intentional. There are some clear markings of swift

changes or

accents. But the intention also lies in the way that the text is divided. Sometimes, when it

gets

more intense, the number of words becomes less and less, so you pay more attention to what

you’re

reading. And sometimes the words are scattered all around—these kinds of things.

So yeah, for me, it’s like composition. In these pieces, I played with words, with their

placement,

and also with the contrasts, and sound was used more as an atmosphere creator.

One neat trick for Unusta is that for the clicking sounds, I sampled vinyl crackling. I

think there are about 60 different samples, and each time you click on something, it randomly

picks

one of the vinyl cracks, which is also something that is a forgetting process. When the vinyl

wears

down, it starts to fade. And in the end, you will only have this noise.

JDT: For me, the topics of both pieces seem to be a bit opposite; one is about memory, and the other is about forgetting.

SS: I think they both deal with memory. Maybe from different sides.

JDT: Is there a difference for you between web-based sound art and composition? And if so, what differentiates them?

SS: I think the biggest difference is the way the pieces are played. Web installations are not

totally fixed; there are some random parameters here and there, but there are no people involved

in

interpreting them; in a way, the audience becomes the interpreter.

But I think that probably the biggest difference is the environment. If you’re in a concert

venue

listening to an ensemble perform, you’re surrounded by other people. I really like the intimacy

of

this internet-based setting, where you can be totally alone if you choose to be. Unusta

was

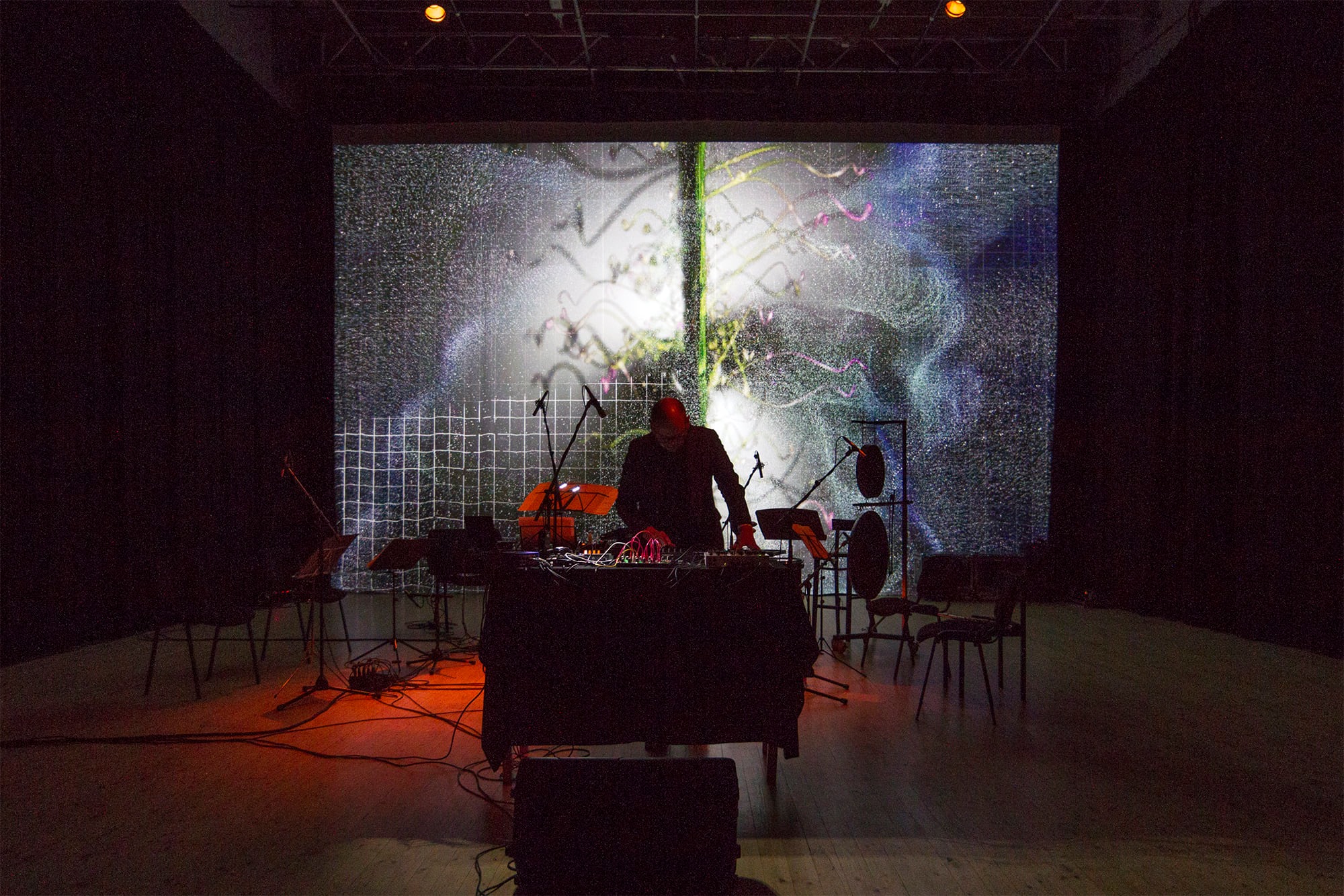

also shown at the Baltoscandal festival. There was a

really cool apartment installation. An old apartment was turned into an art space, and an

Unusta kiosk was put inside the wardrobe. So you had a big screen there with speakers,

and

you could open the wardrobe door and enter this forgetting cabin.

JDT: Amazing! This actually brings me to a more general question, and I am curious to hear your answer. What would be a good way to exhibit web-based sound art?

SS: If it is in any way dependent on interaction, then I think a booth is the best way to do it. Or, you know, if you have video work, you have this black box somewhere, you enter it, and then you just watch it. The same people who commissioned Unusta commissioned another work this year. They put it in an open room with a big screen. There was just one mouse that you could interact with, and anyone could come and play. I think this works well with more visual or auditory things. But for me, my own works are closer to books than to anything else. And it’s something that requires an intimate space. It’s not a public thing.

Screenshot of Unusta

JDT: In these pieces, you are working very much with text. In general, what is for you the thing that drew you/draws you to making web-based sound art? What do you think is very interesting about this medium for you as an artist?

SS: For me, it’s probably just working with text because, in general, I don’t work with it so much. But in this format, it only makes sense for me to use text. Also, it’s a bit like a modular system with this under-the-hood construction. You have these bits and pieces; you have this FM synth that is connected to reverb, but also some granular machine that’s connected to a filter that is sent to the same reverb that you have in the end. You just connect all these little things, but you have to be mindful not to overuse resources because, you know, it is for the web. It’s a cool assignment to try to condense something down to a format that will work on many different machines. But at the same time, have it be high-quality enough to be enjoyed in a larger setting if necessary.

JDT: And what makes something web sound art? What is web-based art for you?

SS: I think the easiest answer would be that the web browser should be the stage. This is where

the

final thing is being witnessed. It can also be that some things happen in real life on a stage

or

whatever, but if the final outcome is seen on a computer screen through the internet, I think

it’s

web art.

Though, if you are simply doing a livestream on YouTube, it’s a concert. A streamed concert. I

think

you should somehow use the platform of a browser and write for it specifically. I mean, I could

imagine some scenario in which you write a piece that you perform as a stream, but then you turn

it

into web art. But if you want to do web art, then you have to think about browsers.

JDT: And how is the perception of time for you in a web-based sound art installation?

SS: Maybe this was one of the selling points of this way of working—that you can actually decide for yourself how you move through time. That’s also the main difference between streaming and some form of interactivity. In streaming, you can just start and stop, but nothing else. You cannot change the inner elements, the pacing of the music, or anything else; it’s just a recorded thing. I mean, you could also create some elaborate, generative patch for the browser that is somehow different each time. I would consider this web-based art as well.

JDT: Do you think interactivity is something that is necessary?

SS: No, not really. I mean, it’s nice to have it, but with generative pieces, it’s not necessary. For me, web-based art doesn’t have to be interactive. It can be, but it doesn’t have to. But it has to evolve somehow and not be 100% fixed.

For me, it felt important to implement some sort of mechanism that makes you concentrate. And I also don’t want to explain everything. I like minimal interfaces, too. Not the way that when you want to start enjoying some artwork or installation or whatever, you have to go through a full manual, and then finally, one hour later, you can start to enjoy it. Also, I feel like it’s fun to explore something about which you don’t know exactly what it is or how it works. But when you get it, then it’s aha!

JDT: Last question. Are you ready? What does the future bring for you? Do you have any web-based sound art ideas that are going to go online soon? What is happening in the next couple of months?

SS: At least this year, I don’t think I’m going to do any web-based sound art, but I’m involved

in

two projects for Salzkammergut 2024. One of them is a VR movie, and the other is an immersive

audiovisual experience on the train. Both are directed by Ella Raidel.

So it might turn into web-based art in the end. There will be an app with a story narrated

through

sound and minimal visual elements, synced with the train stops. So the story will proceed when

you

get to a stop. This will hopefully come out next January. And you can witness it if you go to

Salzkammergut and take a train.

Also, hopefully, next year the new album of V4R1 will be released, and this year I will also

release

an EP under my own name in collaboration with visual artist Liudmila Siewerski.

Photo by Maria Aua, Visuals by Tencu

Your question was also about the future of these things. I think that in the future, a lot of augmented reality things will thrive. So far, it’s always been somewhat clumsy because you have to have a really good internet connection, which can be spotty outside, and also because the browsers still have so many differences that it’s almost impossible to make something complicated work for desktop, phone, and tablet, not to mention different browser standards. I think that this will most likely get addressed and that a lot of augmented reality stuff will start to emerge. Actually, I think I’m quite interested in seeing how it develops. More interested than in VR because VR is still somehow inaccessible. If you go somewhere and there is a line of people who want to use the same headset, it’s too bothersome. I actually prefer immersive artworks where you don’t need to put something on, or where you just enter a space and you’re there, fully immersed.

JDT: Thank you very much for this interview, Sander!

Some resources

website of Sander Saarmets

V4R1’s first album

elektron.art, commissioned Unusta

BALTOSCANDAL, a festival for performative art

Author Jan Kaus on lyrikline

Director Ella Raidel

Visual artist Liudmila Siewerski

Regional Express “an audio-visual-sensory train journey

through the Salzkammergut”

tone.js

To Top ↑